The leather sector is one of the most profitable sectors in Bangladesh and is a major contributor to the country’s economy both domestically and for exports. However, this billion-dollar industry has a problem with child labour. Yet, in March 2021, the Dhaka Tribune reported that the Bangladesh Minister for Labour and Employment declared that six industrial sectors: tanneries, glass, ceramics, ship recycling, export-oriented leather and footwear and silk sectors are free from child labour.

Local leather industry associations insist that their businesses are strictly regulated, and that child labour does not exist in their sector. Is this the case, or is that the Worst Forms of Child Labour (WFCL) exist outside of the regulated sector?

While formal production of branded goods may now be better regulated, the CLARISSA programme has evidenced that the informal sector is rife with the most exploitative and dangerous forms of child labour. Furthermore, the informal sector is likely supplying processed and or unprocessed leather into the formal leather sector and is driving large unbranded domestic and regional markets.

The pandemic

In the shadow of the pandemic, the leather sector is facing huge difficulties and more children are ending up working in the sector than ever. Covid lockdowns caused the closure of most leather supply chain factories and workplaces for three months in 2020. This left children in the leather sector without work and pushed families into crisis, with reduced income impacting their ability to buy food and pay rent. Even in cases where factory owners did not lay off their entire staff, a large-scale decrease in demand for leather products reduced workloads overall and as such many owners reduced the salaries of those workers still in employment.

However, as many industry owners are laying off their higher-paid workers, the pressure remains to continue manufacturing at the same pace. Employers often prefer to employ children because they are cheaper and considered to be more compliant and obedient than adults. As employers lay off adult workers, livelihoods of many families that depended on adult income become more precarious, and, if they were not before, children often become the breadwinners for their families. Many children are faced with the stark choice to undertake dangerous work or starve.

The global reality

At the global level, the International Labour Organization (ILO) has named 2021 the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour and is calling on the global community to ramp up its efforts to end child labour by 2025 – in line with Sustainable Development Goal Target 8.7:

“Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms.”

As the global community is still reeling from the impact of the pandemic, more children are at risk than ever and caught up in the most dangerous and exploitative forms of work.

The CLARISSA consortium recognises the need for this emphasis on child labour, however, we are calling for the focus to be on the WFCL. To do that, evidently, we must look at what most others cannot see – where children are driven to work in the most dangerous and exploitative places.

Hidden in the informal sector

The informal leather sector has many children in WFCL. These informal businesses are in slums and slum neighbourhood areas. Most of these businesses have less than ten workers (including the children) and operate in a working space of less than 200 square feet.

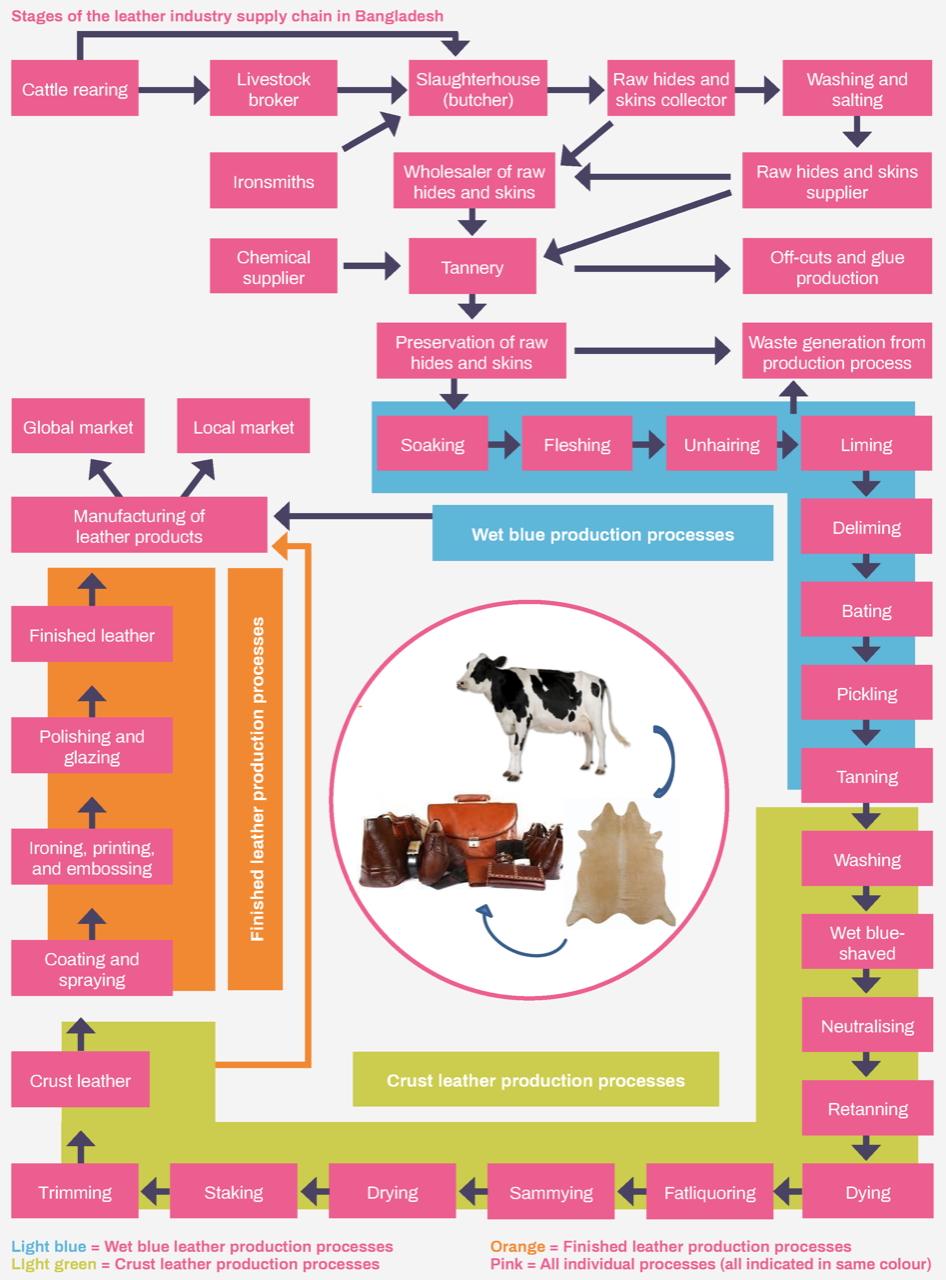

Almost all operate either under sub-contracting agreements with large and medium industries or produce leather products to be sold for the local markets. These small businesses frequently carry out various types of dangerous processes e.g., trading raw hides, preserving raw hides, production of glue, tanning, dyeing, drying, trading, sewing, manufacturing etc.

What is the experience of children involved in the leather supply chain?

- Flaying: Khokon is 17 and works in Kaptan Bazaar, Nowabpur in Dhaka. His job is flaying the cowhides after slaughtering. He also cleans the stomach and intestines of the cattle and disposes of cow dung and other waste materials generated from the slaughtering process.

- Salt cultivation: Raihan is 11 and lives in Mogvail, Cox’s Bazar. He works in the production of salt – during the salt season. During the rainy season, he works as a salt carrier, carrying the salt to boats on his shoulders.

- Cleaning rawhides: Nazir is 17 and lives in Balurmath, Hazaribagh. His job is to wash raw hides with acid. He mixes the acid and puts it into a drum with the hides and washes it for 40 minutes.

- Fleshing: Zaman is 10 years old and works at Gajmahal in Hazaribagh. His job is processing rawhides. He immerses pieces of rawhide in a barrel and adds a mixture of acid, water, chemicals and dye. Following this, he along with some other boys take it in turns to continually rotate the barrel by hand before removing the hides.

- Fleshing and shaving using machinery: Monir, an orphan, is 15 and works at Savar Tannery Industrial Estate in Hemayetpur. His job is de-fleshing raw hides using a large machine. He removes the blade from the machine and sharpens it using a stone. He replaces the blade and starts the machine, laying the hides on a big tray. The hides gradually pass through the machine and the meat and fat residues are removed.

- Pickling: Mostak is 16 years old and works at Savar Tannery Industrial Estate, Hemayetpur, Savar. His job is in pickling rawhides. He dips the hides into a mixture of water and different types of chemicals for 4 hours and then removes them.

- Milling: Rokeya is 11 years old and works at Gajmahal, Hazaribagh. Her job is milling leather for making gloves. Water, soda, acid and other types of chemicals are mixed in a big bucket and the pieces of leather are added to it. She then uses her feet to mix or ‘tumble’ the pieces of leather. This softens the leather. She then washes the leather and carries it up four storeys to the roof to dry, bringing it back after drying.

- Dyeing: Noyon is 11 years old. His main task is to spray finished leather with coloured dye, but he also works in milling, mixing chemicals, drying and trimming leather. He also fetches tea and snacks from local teashops for the factory owners several times a day.

- Embossing: Mehedi is 16 years old and works at Savar Tannery Industrial Estate in Hemayetpur, Savar. For ‘Iron Embossing’ he needs to soften and clean the leather with a vibration staking machine. Then he uses three different plates and a hydraulic leather embossing machine to produce embossed leather.

- Re-dyeing leather: Hemayet is 16 years old and works at Savar Tannery Industrial Estate, Jawchar, Hemayetpur, Savar. His job is to dye leather different colours as required by the buyer. He also carries sacks of chemicals, on his head, between the chemical shop, the storeroom and the dye-mixing drum.

- Manufacturing gloves from finished leather: Rini is 14 and works as a sewing machine operator at a glove-making factory. She assembles the gloves and sews in the lining (ID-007). Momen is 11 years old. He trims excess leather off the gloves with sharp scissors after the sewing process.

- Manufacturing Footwear: Forkan is 13 and works at Gajmahal, Hazaribagh. His jobs are hand stitching boots and glueing soles to uppers. He has become addicted to the fumes given off by the adhesive and regularly abuses ‘Dandy’ (inhales glue fumes from a polythene bag) during his leisure time.

- Manufacturing leather jackets: Yasin is 7 and lives in Gajmahal, Hazaribagh. He works as a shoelace maker. After making the shoelaces he attaches them to the shoes. He also works as a sewing machine operator for jacket making.

- Manufacturing belts: Liakat is 13 and works in Gajmohol, Hazaribagh. His job is to make holes in belts using a small leather punch machine.

- Collection of hair for fuel (Bhushi for boilers): Hasan is 12 years old and works in Gajmahal, Hazaribagh. He works with a production unit that produces glue from hide off-cuts and other parts of the animal. Hasan loads them into a small boiler. After boiling for 2-3 hours, the leather melts and releases a thick, sticky liquid, which exits the boiler through an outlet at the bottom. He collects this in a container and pours it into a tray to dry in the sun.

—

Firoz and Miraz are two tannery workers aged 16-17 years old. One of their tasks was to carry barrels of hydrochloric acid from the shops to the tannery. They would suspend the barrel between bamboo poles with rope, carrying it on their shoulders from pickup point to delivery point. Unfortunately, a year ago they were involved in an accident. The barrel became unbalanced, dropped to the floor, and broke open. Both boys were badly burned, Firoz more so, being closer to where the barrel fell. They suffered burns on their chest, hands, and feet.

After the accident, they were each in hospital for over a month. Their treatment cost around Tk.75,000. The factory owner paid Tk.45,000 to each in compensation and the remaining treatment costs (and their family expenses whilst they could not work) were paid through loans. Initially, these came from other workers at the factory (c.Tk.60,000) which was repaid through a loan from an NGO. Both boys are back at work now and paying monthly instalments towards the loans.

Changing the picture

Far greater attention needs to be paid to the tens of thousands of small businesses which exist in the shadows of the leather economy. Whilst this is much more challenging than engaging with a handful of large exporters, it is essential as the informal leather sector is where the WFCL are found, and this is where the focus is needed. Much greater attention is also needed in relation to the economic drivers that push children into these workplaces.

When we listen to children about the realities they face and ask them to think of solutions, they come up with new ideas that others could never have thought of. Based on emerging evidence on the dynamics of WFCL in the leather supply chain, and in the urban neighbourhoods of Bangladesh, the CLARISSA programme will run targeted, child-led, participatory processes and, in turn, will deliver innovations that will increase children’s options to avoid the WFCL. The findings identified through this work, via the engagement with 153 working children, will be used as the first step in delivering a series of programme activities to counter the drivers of the WFCL in Bangladesh, which can, in due course, be taken to scale.