There is weak evidence of what leads children into worst forms of child labour (WFCL) and many responses simply don’t work. We knew as we embarked on the Child Labour: Action Research Innovation in South and South-Eastern Asia (CLARISSA) programme that WFCL is a “complex” problem because of the multiple drivers, stakeholders and pathways that interact to enable WFCL. We embraced this complexity through use of Systemic Action Research (SAR) as the programme design. We knew that our approach to Theory of Change (ToC) and evaluation had to grapple with emergent pathways and a conventional approach would feel like a straight jacket. We set out to use an iterative and reflexive approach to ToC, making it a centre piece of the programme’s contribution analysis evaluation design and, by extension, the programme’s Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) system.

The development sector as a whole, and the child protection sector in particular are pivoting to greater intentionality in achieving and appreciating systems change, so we should all expect to see greater use of complexity-aware approaches to evaluation and by association, ToC. But are we collectively evolving our use of ToC to be fit for purpose? We know old habits die hard, especially those that afford a sense of command and control in the midst of uncertainty. As we enter the final phase of the programme, and as we launch our latest iteration of our ToC in the form of an interactive online tool, we ask ourselves how well have we really done in meeting our own ambitions?

Moving away from a conventional approach to ToC – the ambition

A conventional and linear approach to ToC assumes we know everything from the outset. It usually doesn’t allow flexibility to adapt the programme according to the changing needs of stakeholders and partners, or a major disruption such as Covid-19. Most programmes spend a lot of time on ToC early on, and only return to it at the end to evaluate their performance against their initial plans.

It is common knowledge now that this approach is not fit for purpose for adaptive programmes that embrace uncertainty and adaptive monitoring, evaluation and learning systems are now becoming more common. Mayne (2015) and Vogel’s (2012) approach to reflexive ToC help us see that a ToC is not just a product (a diagram with a narrative), but rather, it can become a facilitated and critical thinking process through which programme assumptions are made explicit, investigated, and evaluated. Breaking free of the linear straight jacket.

Our ambition starting out was to implement a participatory and reflexive approach to ToC to support real time learning as well as the production of credible evidence about how to respond effectively to the challenge of WFCL. As we near the end of the programme, we reflect on whether we actually managed to escape the straight jacket, or if perhaps too much liberation has created new challenges along the way?

Co-generating high level programme ToC – the starting point

As with most UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) programmes, we included a basic ToC in the proposal – built around a series of starting propositions on the drivers of WFCL that we saw as plausible entry points for participatory evidence generation, such as: ‘actions determined solely by institutions and adults are often inappropriate and don’t meet children’s needs which can result in poor options for children and wasted resources’.

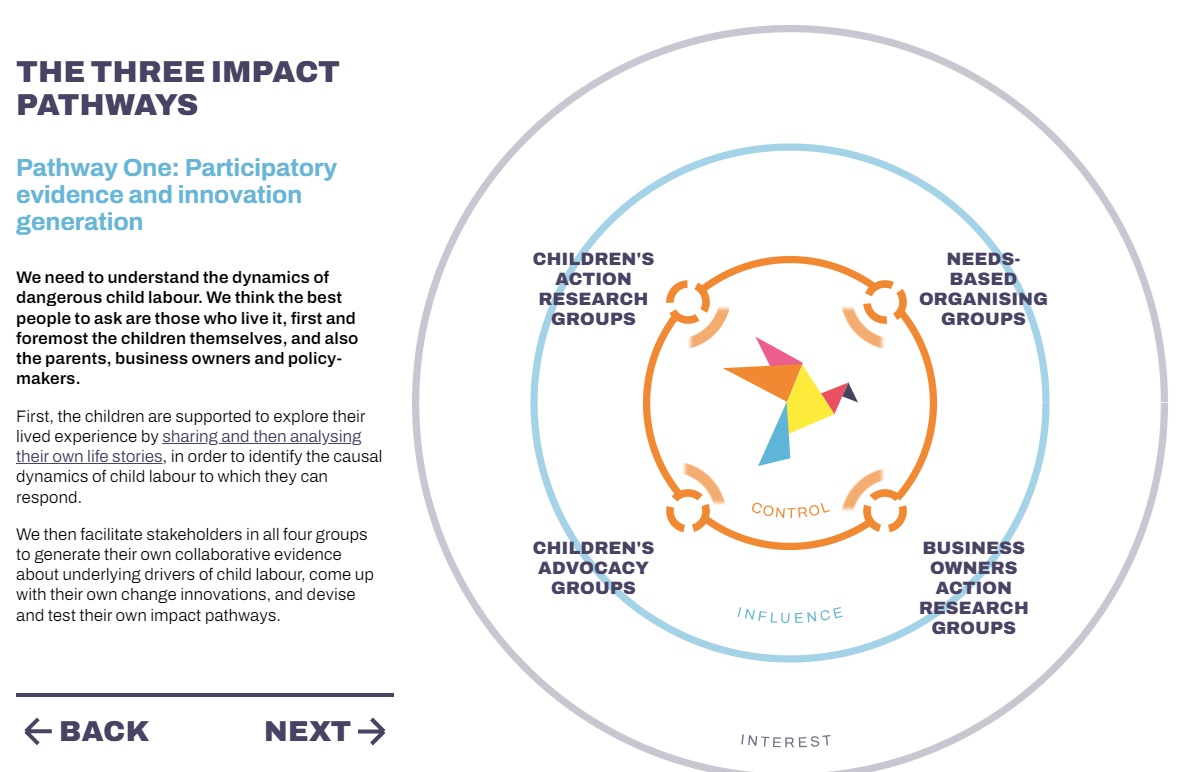

We then had the luxury of a nine-month co-generation phase when we co-designed the programme with partners and FCDO, defining core areas of intervention and building operational teams. This allowed us to ground truth and contextualise the initial propositions and explore what our assumptions were about how change might result from interventions that respond to them. We applied the spheres of control, influence and interest framework from Outcome Mapping. This provides a useful reality check to manage expectations within the programme team on what level of change the programme is aspiring to. It is also a useful framework for negotiating where the ‘ceiling of accountability’ lies in order to agree with the donor the level of change it is reasonable to track, and where we need to employ evaluation research to explore if, how and for whom change is emerging.

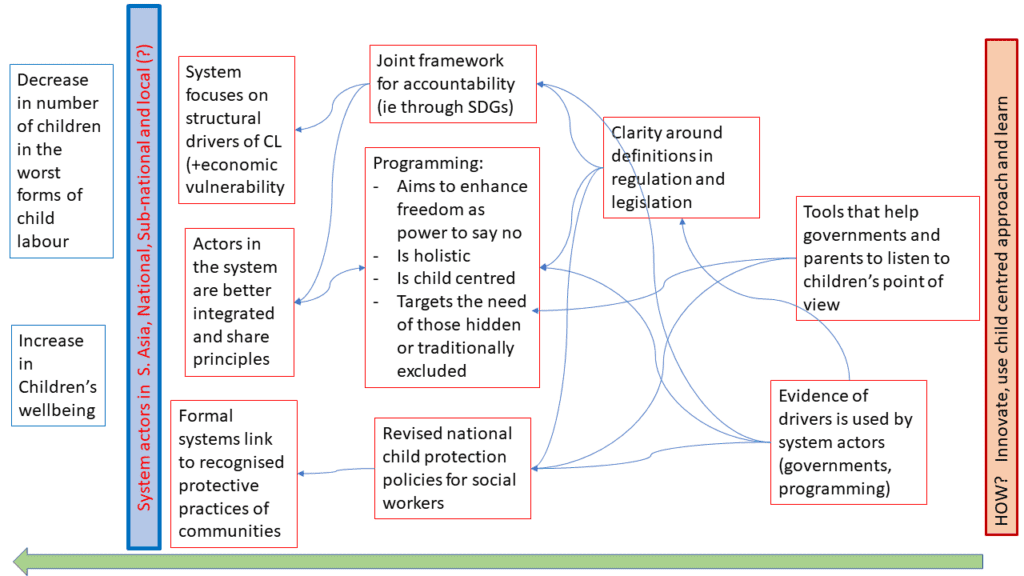

A key moment in moving from initial propositions into a more actionable ToC was a workshop with all partners, including local partners, during which we explored our understanding of the programme’s potential to influence ‘systems change’. In a participatory session we mapped all actors in the child labour programming system and explored pathways to shifting the ways in which they frame the issue of WFCL and consequently how they programme in response and identified our assumptions about how we might influence at this level (Figure 1).

As we have described in this paper, the initial exploration led to some major adaptations in the programme, such as reframing from a focus on large global supply chains to national and largely informal supply chains, which required an adaptation to the original partnership.

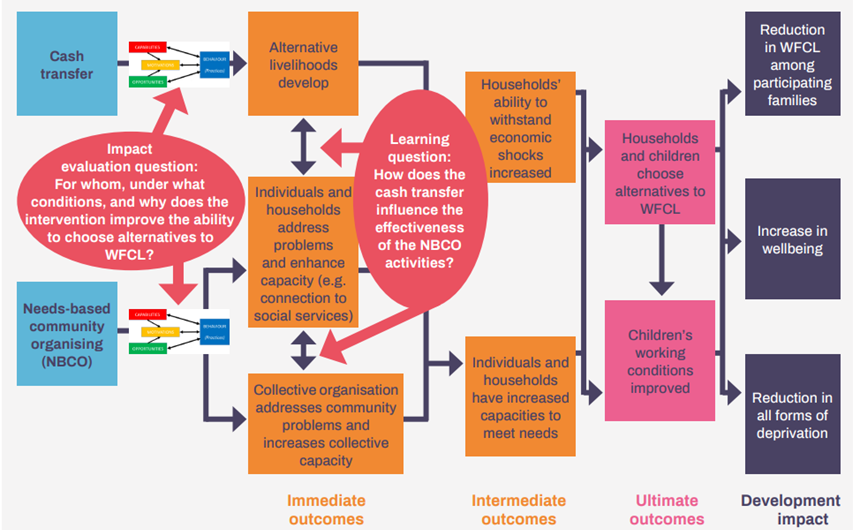

During the co-generation phase the MEL team also worked with each workstream to explore thematic causal pathways while mapping the existing evidence (e.g. on social norms and supply chain dynamics) to identify plausible entry points to respond to the drivers of WFCL. Figure 2 illustrates the initial ToC developed for the social protection workstream in Bangladesh, helping them to define their core learning and evaluation questions.

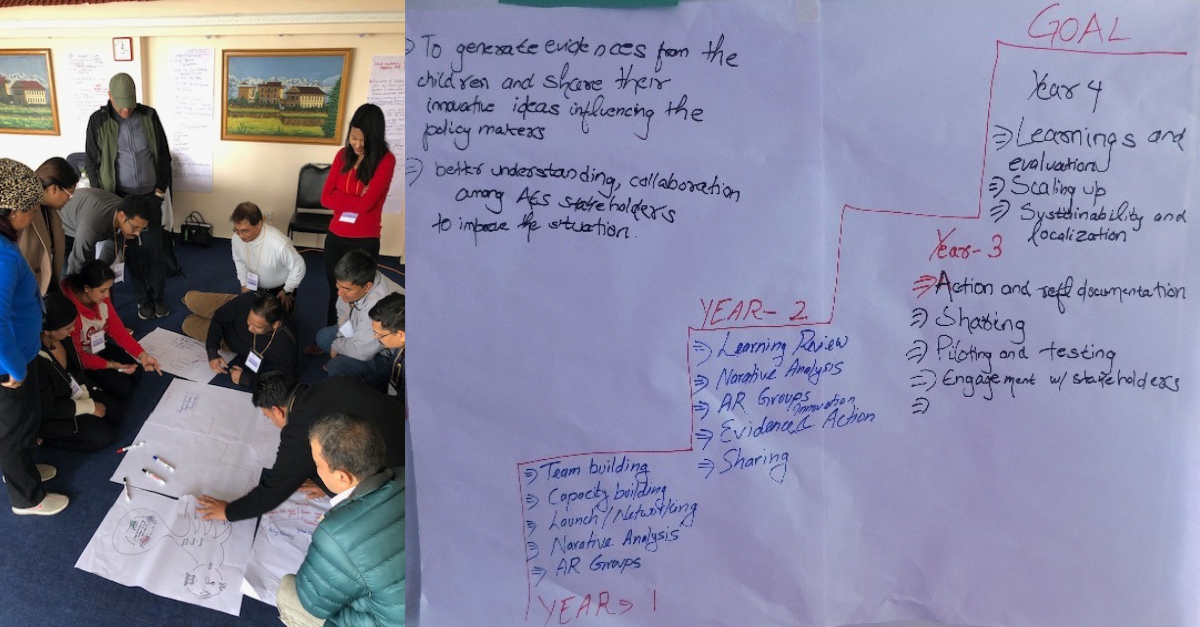

In the first phase of implementation, we then held initial ToC workshops with each country team, and created a vision for success to agree and consolidate our collective ambition and build ownership of the process (Figure 3).

This enabled the teams in Bangladesh and Nepal to have a better understanding of how ToC would be used within CLARISSA, and that the approach was different to other programmes. They were able to critically assess the programme level ToC by both agreeing and disagreeing with the outcome propositions and underlying assumptions as they reflected on the reality in country. Through these discussions, we agreed that a nested country level theory of change would be required to explore how the desired outcomes could work in context.

At the end of the co-generation phase we pulled together all the thinking and evidence reviewed on outcome pathways within each country and linked to all workstreams and produced what we called our ‘best evidenced guess of how change might happen’. This ToC outlines the high-level causal pathways and the assumptions of what needs to happen for the causal links to take place and outcomes to materialise in our sphere of influence. This programme level ToC shaped the programme’s MEL framework, which included an operational learning agenda and defined evaluation questions. It proposed an approach to facilitating learning via six-monthly after-action reviews and evaluating outcomes along emergent pathways including evaluation of the partnership approach and adaptive management. We established a results framework based on this ToC that explicitly avoided the measurement of predefined outcomes beyond our agreed ceiling of accountability.

Navigating operational dimensions of ToC in context

As the programme started to take shape on the ground, we entered a new phase of work, operationalising our ToC and the MEL framework alongside building the participatory processes through the collection and causal analysis of life stories. The children began exploring the pathways in and out of WFCL and the underlying drivers. This led to the selection of specific causal dynamics to respond to through action research, which gave new shape to the participatory interventions to fuel evaluation and learning in concrete directions.

The first challenge we faced with operationalising our approach to ToC came early on, when our non-linear approach hit up against the command and control logic that governs management of NGO programmes by host countries. Both in Bangladesh and Nepal as part of seeking permission to operate, we were expected to produce a conventional results framework with predefined indicators and targets to report on annually to the NGO bureau. We had some difficult conversations at this point, as colleagues who have to liaise with host governments felt uncomfortable. Given their normal linear practice, they struggled to explain that the lack of a log frame was intentional.

Partners also grappled with their own institutional MEL requirements, which in some cases called for cascading indicators down to all donor funded programmes to then aggregate up to meet internal reporting requirements. The solution came in the form of a compromise – a CLARISSA indicator monitoring table that was built by the MEL team using existing partner tools including estimated target beneficiaries that participatory activities would reach, and activity-based indicator tracking. We hoped the lack of outcome and impact indicators would fly beneath the radar to keep the space open for meaningful evaluation of outcomes as they emerged down the road.

Building causal ToC to be fit for purpose

A second, more exciting challenge came when we were ready to design the evaluation research agenda of the programme, building on the now detailed understandings of the thematic areas of intervention in context and responding to our evaluation questions. The solution came in the form of an evaluation co-design process including all partners which resulted in the contribution analysis design along three high level pathways to impact and within them nested causal theories of change for different components. The practice of finding causal hotspots was a useful way to prioritise where to put our evaluation energy and budget.

Reflexivity, how far did we get?

The ultimate judge of how ‘reflexive’ one’s use of ToC is, should be the extent to which ToC becomes a tool for critical reflection and learning. And we know that finding examples of intentional and documented updating of ToCs is a bit like finding a needle in a haystack. So how did we do in CLARISSA?

The overarching high-level ToC of the programme has been revisited, but the revisiting has tended to be somewhat superficial. We have updated our understanding of pathways such as replacing the ‘awareness raising’ assumptions with more agential and action-oriented assumptions about how children are motivated to make different choices. This came as a result of reflections with the programme team during after action reviews in the early phases of the programme. But we have not really made any radical changes to the high-level ToC.

Where reflexivity has come to life, however, has been within the evaluation research components, such as in the realist evaluation of how SAR works, and how Social Protection achieves impact. In the framework of Social Protection when regular monitoring and research data started to come in, we have organised periodic review, reflection and analysis workshops to make sense of changes on lives of the people in the neighbourhood. Through these exercises, with data combined with real life experiences of the community mobilisers, we then adapted the initial impact pathways related to individual, household and group level changes due to needs based community organising and household level change due to cash transfer.

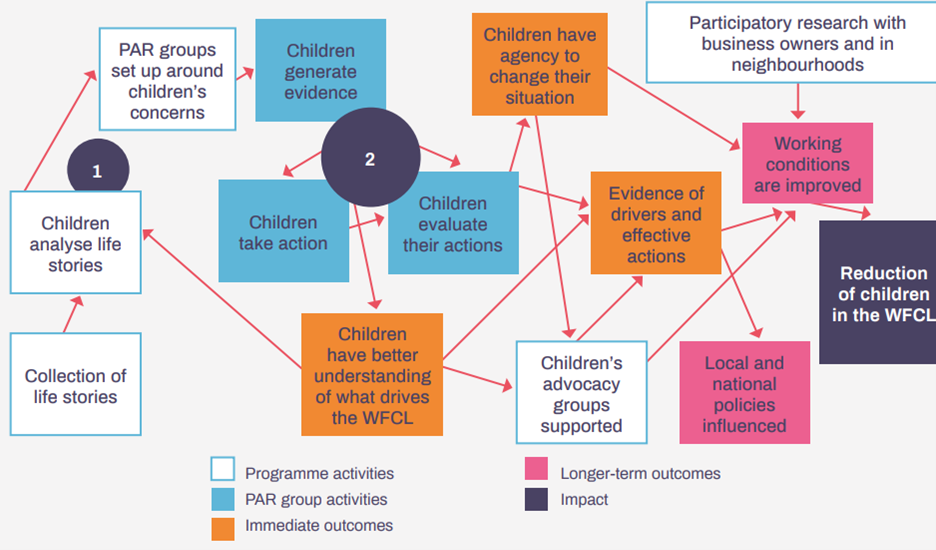

Our realist evaluation commenced with building realist programme theories on how PAR works to generate innovations, based on existing literature, our own expertise on participatory action research approaches and the country teams’ assumptions about how this might work in their local context. These programme theories helped us to zoom further into the causal hotspot as per Figure 4. Through three rounds of collective analysis of the evaluation data with the MEL and implementation teams (one following life story collection and analysis, one following the first 6 months of action research and after the action research groups had finished) we critically reflected on and updated these programme theories. For example, the initial programme theory emphasised that children analysing their own situation will help them see their situation in a new light and develop a critical awareness of what needs to be changed. Whilst we found evidence to support this, what emerged from the data (e.g. children’s reflections and facilitators observations) was the importance of the role of empathy and that the pathway to critical awareness is not just cognitive, but also emotional as children reflected on being able to empathise with their peers after reading their life stories, hearing their shared stories in the action research groups or collecting further data as part of their action research process. Consequently, we updated our programme theories to centralise the role of empathy after our first round of analysis.

Another critical reflection related to our programme theory about ownership of the children over the SAR process. We initially theorised that this critical awareness would result in the children feeling ownership over their problems, the changes that need to be made and the SAR process overall. However, in our first collective analysis we found that children did not experience ownership over the process or the changes that need to be made after they collected and analysed life stories from their peers. In our second collective analysis we identified processes that indicated a shift towards children’s ownership over the PAR group (e.g. conducting meetings themselves, starting to collect experiences from their peers), but they did not fully feel like they owned the SAR process. This then led us to update our programme theories and place ownership further along the causal pathway towards generating innovative actions.

Experimenting with an interactive ToC that can tell the real story

Across the different uses and levels of ToC, we have grappled with how to best visualize the dynamic nature of systemic, nested and emergent outcome pathways. How to visualize theories of change is a hot topic in the evaluation community today as more funders and implementers move towards using theory-based evaluation in the context of systems change initiatives. As Sebastian Lamire and colleagues have shown ‘how we model matters’ and there are countless examples of new and creative ways to deal with this challenge. About a year ago, we engaged a graphic design team to help us develop not just a visual that would help tell our story, but to produce an interactive version that can illustrate our programme ToC in all its messiness.

The interactive theory of change is now on our website and allows users to navigate through the three impact pathways as they play out along the spheres of control, influence and interest and zoom in to particular pathways through the entry point of the participatory processes as well as the stakeholders influenced by them. It shows how impact ripples out and is underpinned by our ways of working.

This version of our ToC is a communication tool rather than an evaluation tool and we hope will become a valuable way to communicate the essence of our ToC to current and potential funders and other stakeholders. It can be updated with new examples of outcomes and learning in the sphere of influence as they emerge. We have learned a lot about how to create a shared and living ToC and we share it as an example of working at the intersections of ToC as a communications and evaluation tool.