The global pandemic has affected communities around the globe causing severe threat to human life and Nepal is no exception. The disease has further exacerbated social inequalities pushing communities into deepening poverty and leaving a profound impact on the lives of most vulnerable especially children and young people working in the Adult Entertainment Sector (AES).

The AES is a thriving sector which includes dance bars, khaja ghar, dohori, disco, cabin restaurants, massage parlours and beauty parlours. It is a sector that is fertile for underaged children to be employed and potentially abused, tortured and exploited. The emergence of COVID19 has just made this more likely as the impact of containment measures impact both livelihoods and economy.

Understanding the real picture

In CLARISSA Nepal, we know too well of the vulnerabilities of the children within this sector, but we wanted to understand in more detail. We conducted a situational analysis to explore the effect of COVID19 on children and to understand their situation. The main objective is to explore the consequences during and in the aftermath of COVID19 to minors working in AES and to understand whether the pandemic could lead to more minors working in the sector.

According to The Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) COVID data in September, there was a total 74,745 cases in Nepal. At the time of writing, there was a total of 19,624 infected, with 54,640 recovered and sadly, 481 deaths. At the end of September, there were 1,351 new infections which shows COVID infection is speedily increasing.

In this context, Kathmandu valley is turning out to be one of the super-hotspots as it witnessed the highest number in a single day crossing over 1000 cases. This reveals the infection is spreading out into the dense cities like Kathmandu valley (Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur) and still the numbers reached for test and trace is way behind than required; and access to medical services is limited. It is a grim reality.

Adverse impact adult entertainment

The entertainment sector is the semi-informal economy booming around urban cities like Kathmandu. Many people wish to enjoy their quality time by enjoying tradition and cultural folk songs, drama, dance, food etc. Over time, in Nepal, the AES has evolved, including features like teasing lady dancers/waitress, erotic dancing, massage parlours and beauty parlours etc.

In their efforts to contain the virus, the government, like many others, forced this sector to completely close down (it has remained closed for almost 7 months). On average over 50,000 workers including minors under 18 are directly involved in this business. While by law under 18’s are not allowed to work in the AES this does not mean it does not happen. Importantly, many studies conducted by academia, research institutions, governments institutions and NGOs/civil societies (pdf) show that children are exploited and part of the worst forms of child labour within the AES.

COVID triggered systematic marginalisation

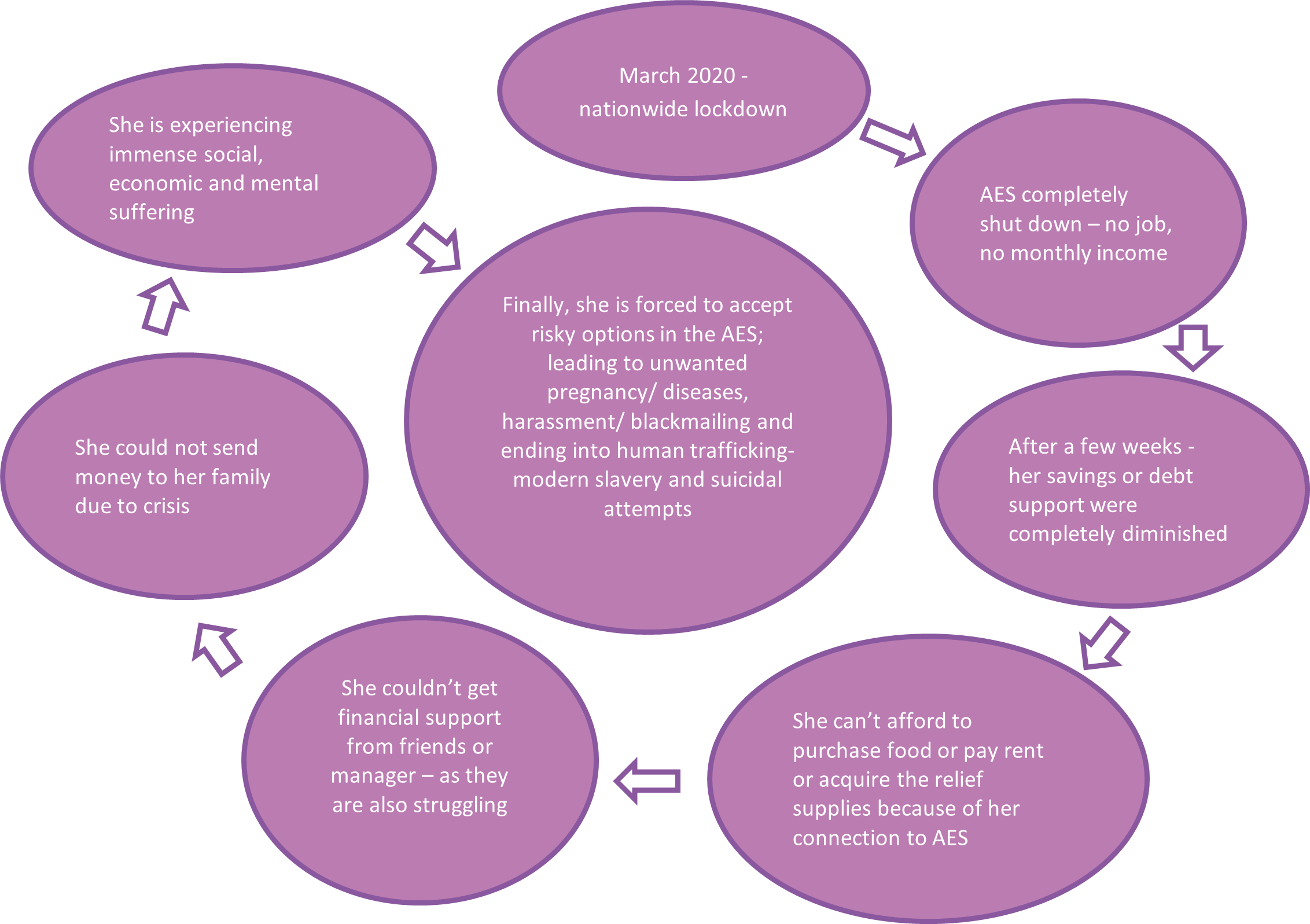

When the Government of Nepal (GoN) imposed complete lockdown nationwide, the AES was not considered a priority area despite the vulnerability of the people that work within it. Let me paint you a picture:

What next?

We are clearly at a very sensitive crossroads – there are 4 urgent steps that the government and other actors need to take to protect the children within the AES.

- Discussion and dialogue among the government, private sector, community-based organisations, NGOs and civil society need to listen and understand AES workers and employees’ voices and their suffering

- Joint action and operational plan. As the pandemic and lockdown has severely affected the AES businesses. The possibility remains high that the exploitation of children will take new form and informal activities, particularly commercial sex exploitation. The National Child Rights Council (NCRC), Labour Office, Law enforcement bodies, Restaurant and Bar Association Nepal (REBAN), Associated Trade Unions and NGOs facilitating project activities need to collectively address this issue.

- Twin-track approach. Despite the formal closure of the businesses, AES workers and organisations shared that there are some activities like commercial sexual exploitation still happening inside the closed venue or space with direct contacts with clients. The government need to implement a twin-track approach, by opening all the sectors and to increase the testing, treatment, counselling and medication services.

- Counselling service. COVID-19 has resulted in mental health and psychosocial pressure on many workers in AES. It is imperative to initiate psychosocial counselling service jointly delivered by the government and agencies working in this sector.

After six long months in lockdown, the Government of Nepal has optimistically decided to reopen the majority of sectors. I welcome this – people need the sectors to open for their basic food security. Yet, the Adult Entertainment Sector remains closed. But the activities that happen within it have not stopped. They have just gone deeper underground and children are more vulnerable than ever to participate in them, but without any protection at all. Going forward, there need to be clear guidelines and enforcement of COVID measures in the best efforts to prevent transmission, but this must be alongside a reopening of AES. We must protect children from the worst forms of child labour, especially in COVID times.